Throughout his life, David Livingstone was a prolific writer. Yet until the 1970s, no one knew the full extent of his work. A number of well-known British and African archives held original Livingstone manuscripts. Some manuscripts came out of the woodwork, were sold at auction, then vanished back into the ether. Several individuals, notably Isaac Schapera, had published edited collections of letters and other items, but there was not yet a complete and authoritative print source for Livingstone’s manuscripts.

Everyone with a serious interest in Livingstone recognized the need for a full compilation to bring together all of these items. The Livingstone Documentation Project (1973-1985), launched out of Edinburgh, first sought to address this need. The project produced David Livingstone: A Catalogue of Documents (1979) edited by Gary Clendennen and Ian Cunningham, followed by a supplement a few years later (Cunningham 1985).

The Catalogue and its supplement for the first time brought a number of key points to light. First, they confirmed that Livingstone had indeed written prolifically, probably more so than anyone had imagined. The original Catalogue enumerated the following:

· more than 2,000 letters

· 11 substantial journals

· 39 field diaries of various sorts

· 18 notebooks

· 30 papers and reports

· almost 200 other miscellaneous items

The Catalogue also revealed that these manuscripts were scattered around the world – among some 90 repositories in Britain, Portugal, France, New Zealand, the United States, and several countries in Africa. Many, many other items remained in unknown, private hands.

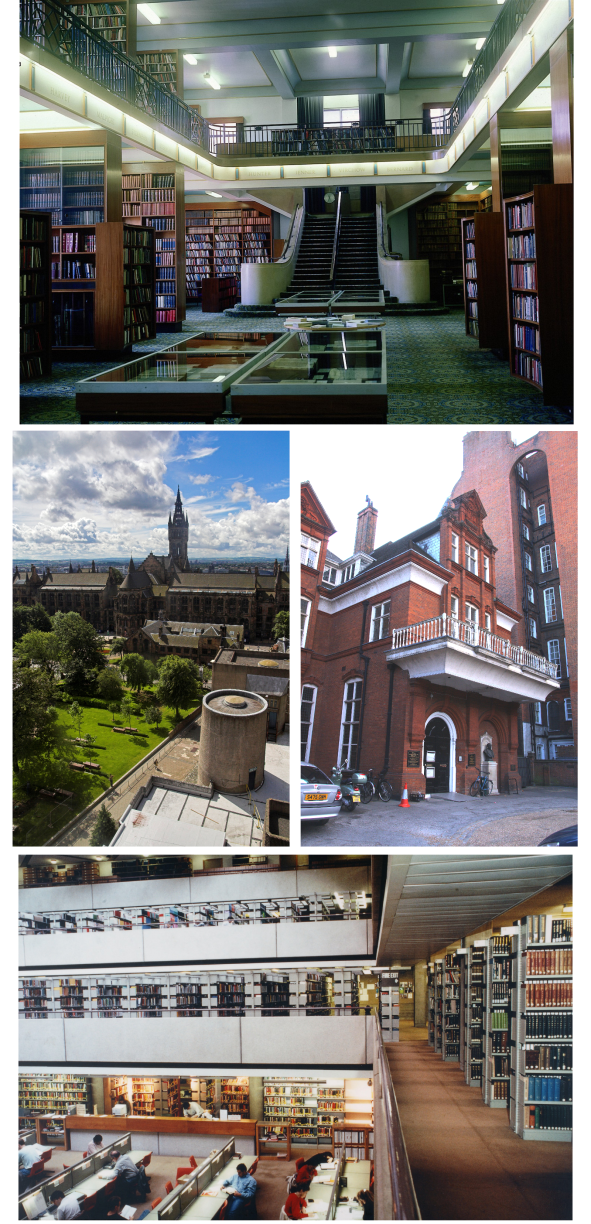

When it launched in 2005, Livingstone Online took up the work of the documentation project. The team identified some thirty previously uncatalogued items and produced an integrated and updated digital version of the original print Catalogue and its supplement. The site also began to partner with repositories (nearly 30 to date) that held Livingstone materials in order to produce digital versions of these materials. Between 2005 and 2013, Livingstone Online acquired some 4500 images of original Livingstone manuscript pages as well as nearly 500 images of objects related to Livingstone’s travels or of repositories holding his manuscripts.

The work of the Livingstone Online Enhancement and Access Project (LEAP, 2013-2016) further continues these initiatives. Although LEAP formally launched just last September, we have already collected information on some 70 previously uncatalogued items, including maps. Moreover, the University of Glasgow Photographic Unit is just now – on our behalf – working full steam to digitize the manuscript holdings of the David Livingstone Centre, and the National Library of Scotland has just this week generously delivered a huge cache of Livingstone images to us as well.

We’re still make our way through all this material, but we look forward to releasing all of it through our updated project site in the near future. If you happen to know of any items that you think might not yet have come to our attention – for instance, uncatalogued Livingstone manuscripts are rumored in Angola, Mozambique, Tanzania, Malawi, and elsewhere around the world – do drop us a note….