Kate Simpson (Edinburgh Napier University), author

In the first chapter of Missionary Travels (1857), David Livingstone writes about ways to stop the slave trade in Africa. He talks of trying to bring all people into “the body corporate of nations, no one member of which can suffer without the others suffering with it.” It is this surprisingly contemporary understanding of cultures and how they engage with each other that makes David Livingstone so interesting. This understanding of agency and mutual interest is also why I was so keen to explore this seminal book further. I was given the perfect opportunity to do so – just as my PhD was coming to an end in 2016 – by working with Justin Livingstone and Adrian S. Wisnicki on a digital edition of the three-volume manuscript of Missionary Travels (1856-57).

In October 2016 I began a one year Modern Humanities Research Association (MHRA) Research Associateship in the School of Arts, English and Languages at Queen’s University Belfast, where Justin Livingstone (the PI for my associateship) teaches. This was a fantastic opportunity for me as it enabled me to not only engage with the fashioning of the story of Livingstone’s first fifteen years in Africa, but to be involved in the creation of a unique digital critical edition – one in which the user was invited to read a book through its preparatory manuscript. This edition (forthcoming from Livingstone Online in 2018) will allow users the opportunity to follow the creation of Livingstone’s narrative as he, and the many other editorial hands involved, worked to turn the manuscript into what would become one of the most famous travel books in Victorian Britain.

Missionary Travels (1857) is a special book in the history of British exploration. It was not only one of the bestselling books of the mid-nineteenth century, but it shaped British ideas of the archetype of a missionary-explorer, a seemingly indomitable figure crossing continents unsupported and on his own. Yet it is also a text in which the obligation and reciprocity of the expeditionary encounter is highlighted. Livingstone would never have been able to make the journeys he did had it not been for the people – such as Halima and Manenko – who negotiated travel rights on his behalf, helped feed him and his party, and willingly gave their time to guide and support him.

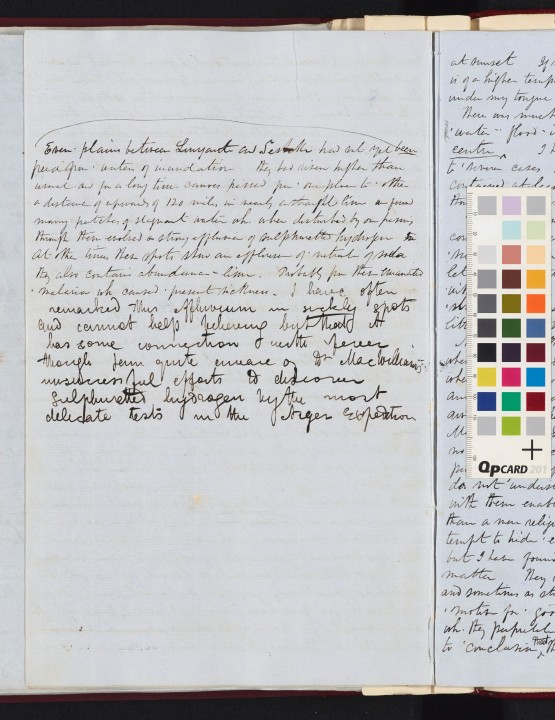

The manuscript of Missionary Travels consists of 1135 pages spread across three bound volumes. The original manuscripts are held at the National Library of Scotland, and the images of most of them were delivered as an in-kind contribution to Livingstone Online as part of the recently completed project called LEAP (2013-17). The manuscript is particularly interesting as it is rare to have such a complete pre-publication manuscript of a nineteenth-century exploration narrative, especially one in which it is possible to identify the various hands which crafted the narrative. It is also rather exciting in that it contains material which never made it into the original publication, but which we will now, through the work done in this project, reveal.

The fully transcribed manuscript of Missionary Travels will make available for the first time the story of the construction of one of the English language’s most famous travel books. It will allow users to see the mediated circumstances of the book’s construction and encourage readers to approach the text in new ways.

The high quality images of the manuscript pages will encourage the user to look not just at the words which made it through the publishing process but at the actual construction of the published book itself. Detailed transcriptions and annotations, moreover, will assist users in reading this complex manuscript. Users will, for instance, be able to clearly identify the different scribal hands engaged in producing the text, such as that of Charles Livingstone (David Livingstone’s brother), as well as the various editors who were involved in correcting the manuscript.

My role in the digital edition of Missionary Travels focused, among other things, around the creation of a digital surrogate of the published book itself: the text that users will be able to link to as they read the manuscripts. Although previously I had been involved with the transcription of the manuscript, the associateship allowed me to uncover quite how much the original manuscript differed from the final published product.

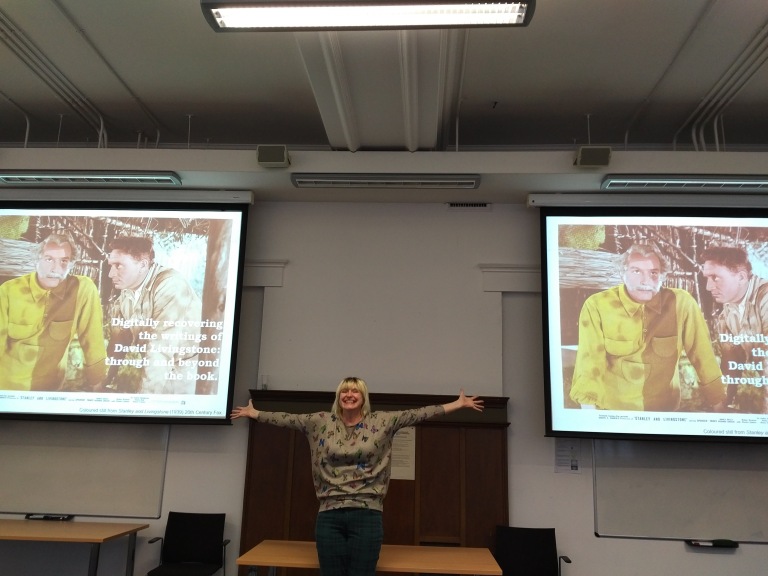

The associateship also enabled me to travel, meeting up with other Livingstone researchers and fellow digital humanists. At the very start of my associateship, I was invited to give a guest lecture at the University of Glasgow in which I talked about the importance of the digital edition, its ability to reveal hidden or muted information in the primary documents, and its role in critical studies. The content for this lecture emerged out of the many meetings of the project team in which we discussed what we wanted the edition to be able to do and how we would enable user interaction.

One of the highlights of my fellowship was the opportunity to travel to America for two weeks. Project director Justin Livingstone and I were able to meet with Livingstone Online director (and co-PI for my associateship) Adrian S. Wisnicki at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL) to discuss the development of the critical edition and to receive training in CSS and XSL coding. Justin and I also gave a lecture at UNL in which we were able to share our exciting work with Adrian’s colleagues and post-graduate students.

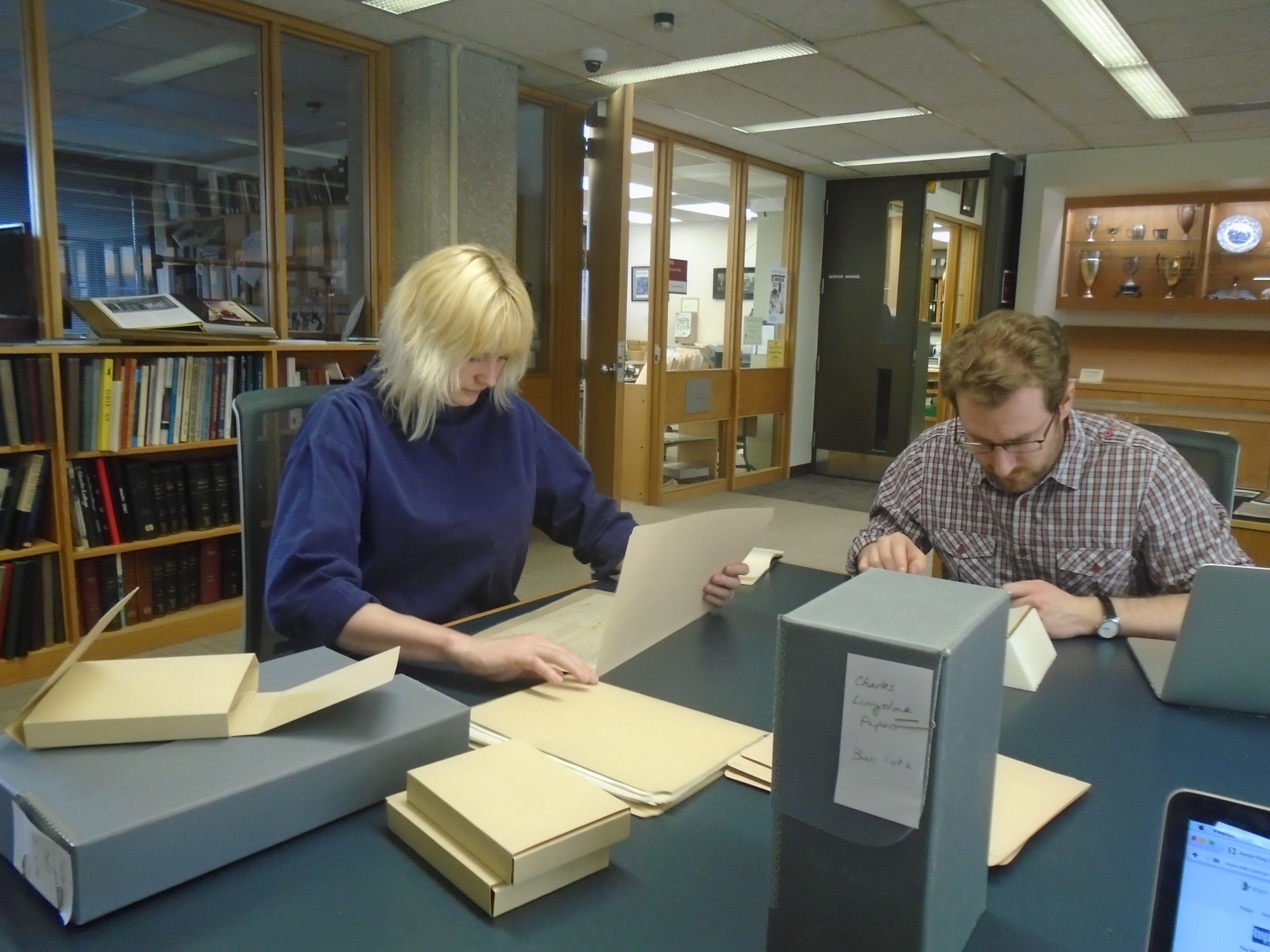

Whilst in America, I also traveled with Justin and Adrian to Oberlin College in Ohio, where we began preliminary research into Charles Livingstone’s manuscripts from the Zambezi expedition (1858-64), held in Oberlin Library’s Special Collections. Charles studied at Oberlin for a time in the 1840s. In Ohio, we had a series of team meetings with fellow long-time Livingstone Online collaborators Mary Borgo and Heather Ball. These meetings focused on a proposed project on the Zambezi expedition and other projects currently ongoing underneath the umbrella of Livingstone Online (such as a critical edition of Livingstone’s surviving manuscripts in South Africa).

What struck me most forcefully at this point was how much we, as colleagues, mirrored Livingstone’s international-ness. Our site is not nation-bound. In fact, like Livingstone himself, Livingstone Online is peripatetic. Collaborating through version control sites like GitHub, we have been able to remotely work together creating, editing and shaping content. But it was just as fun to sit side-by-side working together – but separately – on the same content.

Just prior to our work in America I was invited to give a two-day, TEI best practice workshop in Beer-Sheva and Jerusalem. Using the skills I had gained in my time as a project scholar for Livingstone Online and, most recently, in planning and encoding the published version of Missionary Travels, I was able to share project work with colleagues from Germany and Israel. This open source open access scholarship is one of the most defining characteristics of the Livingstone Online project. Being able to explore and engage with people about our work and its place in the wider remit of digital humanities scholarship was a hugely fulfilling part of the project.

What I have always loved about Livingstone Online is its very open-endedness. Our work on Missionary Travels has not focused on creating an absolute reading or reinterpretation of the text. Rather, we have created an electronic edition and digital apparatus, one open to being used in multiple ways. Our digital scholarship has helped the process of unpacking narratives of European exploration by enabling us to track and display the precise changes made to one of the most important expeditionary narratives of the nineteenth century.

I wish to lay my profuse thanks at the doors of Justin Livingstone, Adrian S. Wisnicki, and the MHRA for enabling me to be part of this project. This past year has been awesome. I wish I could do it all again. Digital scholarship has allowed me access to the human creators behind the formation of the story on the physical page. How cool is that!

One thought on “Missionary Travels – from Page to Screen”